Ella Segal would wrap study materials in opaque bags so that no one would identify them ■ David Kook said he wanted to study history so that they wouldn’t laugh at him ■ Four Haredi medical students explain how they integrated, against all odds, into the most prestigious field there is

Ella Segal (24) knew from a very early age what she wanted to do in life. “Already as a little girl I was drawn to the sciences and dreamed of studying medicine,” she says. Her parents knew about this and supported her, and she started trying to figure out ways to be admitted to medical school. “During a visit to the pediatrician when I was 13, I asked what to do in order to be accepted. He told me: ‘Study English and mathematics at a high level.’ That was very good advice.”

So far, this is a standard story of a medical student. But Segal is a Haredi woman from the Lithuanian stream, and as a girl from B’nei Brak, becoming a doctor was not supposed to be her dream.

Haredi girls do in fact study English and math for more years and at a higher level than boys, who attend yeshivas, but in the high school where Segal studied, a Beit Ya’akov, matriculation exams were not given, and the level of English and mathematics was equivalent to only three units. This, of course, was an impossible starting point for anyone who wants to pursue academic studies – and certainly in order to be accepted to most prestigious academic track at university. “I wanted to do the matriculation exams but I couldn’t; there was simply no such option at our seminary,” Segal says.

Determined to make her dream come true, Segal found a creative solution to the challenge: a detour around matriculation. At the end of high school, while she was still studying at the seminary to become an English teacher, together with her friends, and without telling practically anyone, she registered for the Open University – which does not require matriculation or psychometrics – and did a bachelor’s degree in life sciences. “It was a complete secret. Only my closest family knew about it. When materials with

the university’s logo would arrive at the post office, I would wrap them in two opaque bags and take them home from. It was only toward the end of my studies that I told my close friends and extended family. But until this day, not everyone who studied with me at Beit Yaakov knows about this.”

What would have happened if your friends or someone at the seminary had known about it in real time?

Segal: “I probably wouldn’t have remained at Beit Yaakov, and that was important to me, because I really liked the place.”

Segal completed her bachelor’s degree magna cum laude in four years and was admitted to the four-year bachelor’s degree medical studies program at the three universities to which she applied – Tel Aviv, Bar-Ilan and Ariel. She also obtained rabbinic approval for her highly unusual procedure in a creative way: “I consulted my rabbi, who is my father, and he gave his approval. She is now finishing her sixth year at Tel Aviv University’s medical school and is deliberating where to apply for her internship year.

“Haredim need to become involved in all areas of life”

The number of Haredi doctors, both men and women, in the world of medicine is still negligible. The reasons are clear: the chances of a young Haredi man who did not study core subjects or a young Haredi woman who studied English and mathematics at a low level being admitted into a field that even graduates of the most prestigious high schools find it very difficult to get accepted into – it is virtually nil. And this, even before taking into account equally great obstacles, such as gender-mixed classes, which are only the first step on a career path and lifestyle that are in stark contrast to the sheltered and separate Haredi way of life. In addition, medical studies take many years, during a time when Haredim focus on building large families, so that strong financial support is essential – but most Haredim live on a very low socioeconomic level.

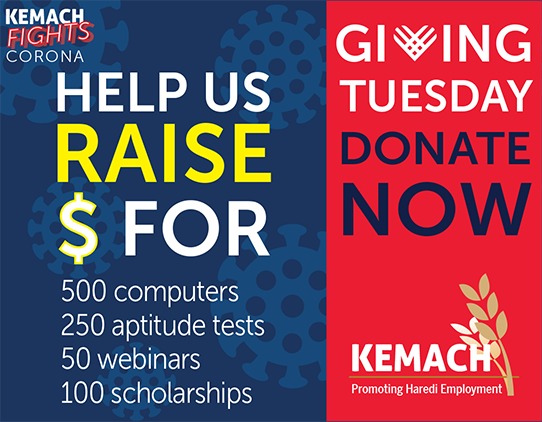

At a time when the prospect of expanding core studies in Haredi educational institutions is diminishing due to the coalition agreements, the chance of Haredi girls and boys studying medicine is growing ever smaller. And yet, despite this complex reality, there are young people in the Haredi community who want to conquer this summit without giving up their Haredi way of life, and they receive formal help from within the community. For example, the KEMACH Foundation is a Haredi organization that receives government funding and encourages Haredi employment through grants, career counseling and career guidance. It has been in existence for over a decade and several years ago expanded its activities into a field to which only several hundred select individuals with almost unreal grades succeed in being admitted to every year. “In Israel there is a shortage of Haredi doctors; we identified a severe underrepresentation,” says KEMACH Vice President, Avraham Yustman. “Looking ahead, we think that we Haredim should enter all areas of life – including medicine.”

The foundation offers budding doctors career guidance and support, and if necessary, study and subsistence scholarships: “It is a large and ambitious project, because the studies are intensive and demanding, and it is necessary to offer significant financial assistance,” says Yustman. “The moment we made scholarships available, we created more demand on the part of the Haredim; otherwise, it is very difficult to study medicine. Today, there are already 30 Haredi medical students at various stages of their studies, 19 Haredi doctors, both men and women, who received financial and professional assistance from KEMACH, and dozens more who applied for the coming year.

David Kook (30) from Netanya grew up in a Chabad family and studied in a yeshiva where core studies were not taught. “In elementary school, I studied basic math until grade 6, and barely knew English,” he says. At age 19, he enlisted in the IDF, serving a full three years as a medic in the Golani Brigade, but didn’t dare dream of studying medicine, because “I didn’t think there was any chance of my studying anything like that.” After his discharge, he became a Chabad emissary in Mexico and Guatemala, and then went on to a Chabad yeshiva in New York. The usual track in Chabad is rabbinic certification, marriage, study in a kollel and work. But Kook had other dreams: “At the age of 22, I decided that I wanted to study medicine, but I didn’t exactly know where to start.”

So he started like this: “I went into Google and wrote, ‘How do you get accepted into medical school.’ I saw that you need to pass the psychometric exams, but I didn’t know exactly what that means. So I typed into Google, ‘Sample exercises for psychometrics,’ and got a list of exercises. When I return to Israel, I enrolled in a psychometric preparatory course and they asked me what I wanted to study. I said ‘history,’ because I was afraid that if I said medicine, they would laugh at me. They responded: ‘Okay, we’ll work really hard with you and you’ll get a 500.’ We really worked hard, and I scored over 700. Afterwards, I improved and got an even higher grade.”

Kook’s matriculation exam story was similar: “I did a regular preparatory course at the Hebrew University, because I didn’t even know there was a preparatory program for Haredim. This was a course that people attended to improve their already excellent matriculation exam results in order to be accepted into the most difficult courses of study, but I hadn’t even done the matriculation exams. After two months, I went to the secretary and told her I wanted to study medicine. She advised me to take the most basic preparatory course, to get a first degree – and then to apply for the four-year medical studies program. I also contacted the course coordinator, who was a lecturer in physics, and he told me ‘don’t leave.’ So I stayed and studied, and every time he said something that I didn’t understood, I would check it out in Wikipedia – and in this way, I progressed. In the end I got a high grade in the preparatory course, improved my psychometric score, applied to medical school at the Hebrew University and was accepted. Next week I’m starting my internship at Laniado Hospital in Netanya.”

Kook says that before he started his studies, he consulted a rabbi “about everything” – questions about studying in mixed-gender classes and about specific dilemmas: “For example, about doing dissections [autopsies, which are part of anatomy studies; RL]. There were religious guys in the class with me who got permission. The rabbi I went to asked me what I need to do in order to learn and I explained that I needed to see everything and he told me to be in the room, but not to touch the corpse.” Kook admits that “it wasn’t easy, because I want to be a surgeon and I wanted to have the experience, but there will be many other opportunities.”

“Culturally you are still an anomaly”

Tsila Reichman (24) was also raised in a Chabad family and studied at Chabad institutions in Be’er Sheva. She, too, dreamed big from a young age. “I knew I wanted to be a doctor. My parents are ba’alei teshuva, my father is a family doctor and my mother a nurse, so I was exposed to the world of medicine, and my parents supported me and encouraged me. I believe that if a person does not take advantage of his talent, it is a waste, and if I can – then why not?”

Despite her determination and the support she received, Tsila faced a major obstacle that was beyond her control: “At the Chabad high school for girls in Be’er Sheva where I studied, they take matriculation exams for the purpose of being admitted to a teachers seminary, but only at level 3 or 4. I asked to do 5 units in English and math, but they explained to me that they would not start a major for only one girl. So with the help of private tutors that my parents hired, I did 5 units and took the matriculation exams.”

How did they react at school?

Reichman: “They didn’t really believe that I would succeed, because I had to make up eight weekly hours of material in math and more hours in English, while attending school as usual. But I was very sure of myself, and I explained to the principle that this is what I want to study in the future. I am a very respectful person, and when you respect your surroundings, you receive respect in turn. I took the matriculation exams in the first exam session and received an 80 or something like that, and I was so upset that I said I would do it again. The teacher said to me: ‘What do you want to get? 100?’ The second time, I got a 99. I also had a teacher who thought that if I started studying at the university I wouldn’t be so Hasidic and would stray from the path (I would become less religious; RL). At the end of the year, she apologized and told me ‘well done’ and said that she hadn’t believed it was possible to pursue general education and stay on the path.” The second time Tsila took the psychometric exam, she received 710 – which, combined with her high matriculation exam grades, was enough for her to be admitted to dental school at Tel Aviv University.” Today she is in her fifth year, out of six years, of study at Tel Aviv University.

Tsila’s husband, Avraham Reichman (27), is an intern in medicine. He was born and raised in Texas to a family of Chabad ba’alei teshuva. His father is a doctor and from

childhood, his parents encouraged him to study for an academic profession alongside his religious studies. Such a goal is easier to achieve in the US: Avraham did indeed study in Haredi yeshivas his whole life, but in the US, Haredi boys also study core studies, including mathematics. “The most Haredi people there study at this school,” he says. He did his first degree in biology at Yeshiva University, an Orthodox institution that combines religious studies in the morning with academic studies in the afternoon.

After finishing his first degree, Avraham applied to medical school in the US and also to the Technion American Medical Studies Program, designed for students with a bachelor’s degree. He was admitted to the Technion and during his studies, worked as a physician’s assistant at the Asuta Hospital in Ashdod. He now lives in Be’er Sheva and is doing an internship at Soroka Hospital, after which he will do a residency in internal medicine. The couple has a baby of one year and two months.

“It’s not suitable for everyone”

The difficulties for young Haredim who are accepted into academia’s elite program continue and possibly even increase during their studies, as enormous challenges present themselves. People who grew up in a kind of bubble, apart from the secular world, with gender segregation and strict rules, now must live in a completely different world.

“It’s not suitable for everyone,” says Kook, “for a person who maintains a Haredi lifestyle, it’s not a natural environment. I served in the army with secular and religious people, and the preparatory program I did before my academic studies was also aligned with the outside world, but you are still a cultural anomaly. I’m quite a sociable person and I’ve integrated socially, but you still look different and your lifestyle is different.”

“It’s a bit strange for example to study together with men or to be exposed to another culture,” says Tsila.” But I came with support from home, and I know that I’m here to learn and I have a goal, and when you have a goal you are more likely to stay on track. People are very respectful, but some people are more aware and others are less. For example, in the beginning there were boys who patted me on the back. It sometimes creates socially embarrassing situations, but slowly people begin understand. They already know not to curse near me.”

Segal talks about another type of challenge: “I don’t know and have never had access to a doctor, a medical student or anyone connected to the medical profession, so I have no one to consult with or to learn from. Everything in academia is new to me. I arrived at university with no idea of how to write a paper. Talking to patients was also difficult at first, although as a student in my last years and as a physician’s assistant, I am constantly meeting patients, and today it is much easier.”

All four of them talk about Shabbat as one of their biggest challenges, for example, when they have an exam on Sunday. “Even ordinarily, we have one less day to study, so exams on Sunday after Shabbat is an additional difficulty,” says Avraham. “On the other hand, the fact that we got used to studying Torah for hours on end in yeshiva helps us now.”

“Starting next year, my internship year, I am going to work on Shabbat,” says Segal. “This entails both religious and emotional issues. To me, as a woman, Shabbat is the most amazing day of the week, which I look forward to already the previous Saturday night. I know that working will ruin something for me – the very fact that I’ll be walking around with a mobile phone, that I’ll have to write on the computer, the entire routine. But in a way, I’m also looking forward to it, precisely because it is permitted and mandatory to rush to help the sick on Shabbat – I want to be the person who offers medical assistance.”

Sometimes the challenges come from home: “When I had just started studying, someone told my mother that she wanted to introduce me to someone who also became irreligious,” says Tsila. “People thought that if I was studying medicine, I’m for sure no longer religious. Now you can see that I’m still Haredi. I dress the same way as before and go to synagogue. At first there was more suspicion and people weren’t sure what was happening.”

Segal: “There’s a scale of reactions. There are people to whom it is strange and who don’t know exactly what to make of you. They say to me – ‘Well you’re American, you’re from abroad,’ or ‘you’re a ba’alat teshuva,’ but I grew up Haredi in B’nei Brak. Or when I say that I’m studying medicine, they say – ‘Oh, a nurse.’”

To the KEMACH Foundation, the question of whether the young doctors remain Haredi is critical: “The personal example is a very important element of the success stories of Haredi employment,” Yustman says. People see a Torah giant and they want to emulate him. The same principal applies here too: the key to the program’s success is that others see that they do it and remain Haredi. It’s part of our DNA, and we try very hard to achieve that. We also have a program to preserve Haredi identity called Avnei Derech (Milestones), which meets weekly to study Torah and to talk about difficulties in academia.”

Let’s say you invested money and effort in a Haredi medical student and he suddenly is exposed to the outside world and decides that he doesn’t want to be Haredi anymore. What does that mean for you?

Yustman: “It would be a total failure. We had a discussion about that because people become acclimated to different social groups and there are temptations. That’s why

expanding the program to include more young Haredim depends on the fact that the talent remains Haredi, that the father of the next young man or woman sees that the others remains Haredi. Otherwise we are in trouble, because then it will come back like a boomerang.”

That is, they will blame you, and say that specifically because of this program, young people became non-religious

“Yes. We feel that we are constantly being held accountable. The day I fail like that I will be in trouble also with myself, because I will understand that something in my mission isn’t working properly.”

Students, you have a great responsibility on your shoulders

Kook: “With all the individualism, we live in a framework and have responsibilities. I’m quite mature, and I made decisions about my life and decided where I am.”

“Core studies are not a key parameter for me”

When you talk to the four young people, who are imbued with motivation and love for their profession, it’s easy to forget that they are an extremely unusual phenomenon in Haredi society, and have four unique personal stories. They succeeded in overcoming a long list of obstacles – from the lack of core studies and a basic knowledge of mathematics and English, to overcoming the challenges of gender-mixed studies, autopsies and working on Shabbat. The common denominator they all share, besides natural talent and courage, is a supportive family that is not put off by academia or the reactions of the conservative environment.

It is also difficult to ignore the fact that our meeting takes place during a period when core studies in Haredi educational institutions – or rather their absence – are in the headlines and in the eye of the storm, after it was decided to remove the requirement for core studies as a condition for receiving government funding for Haredi schools. In other words, in the coming years, Haredi boys and girls are actually going to be farther away from the dream of one day reaching the pinnacle of academia – medical studies.

Surprisingly, those who managed to penetrate the ivory tower after enormous efforts and great difficulties are not necessarily in a rush for their children to do the same: “My son will study in a talmud Torah and a yeshiva (that is, without core studies; RL),” Kook says. “The Lubavitcher Rebbe was asked about this many times, and he said that at this age it is very important for a child to acquire a set of values and at a later age he can complete what is necessary.” Segal says, “Core studies are not a key parameter for me, maybe in the fourth or fifth place. It’s more important to me that he learns how to learn and most important is the peer group with which he is studying.”

Even Avraham, who studied core subjects as a child in the US, says, “I also think it’s not the most important thing.”

The only one who offers a different opinion is Tsila: “It is important to me that he learns math and English. It’s true that won’t determine whether he’ll be the genius of the generation, but it is important to broaden horizons. If he doesn’t study core subjects in yeshiva, and unfortunately, there are almost no yeshivas that invest in math studies, I’ll get him a private tutor.”

“Haredi society is aware of the price that it pays for the lack of core studies and it is also clear that there is no religious problem with English or mathematics, which are ‘pure’ subjects. But the perception of the majority of the Haredi public in Israel is that you should devote all your time to Torah study, certainly from bar mitzvah age. It’s one of a person’s religious obligations and it shapes him,” says Yustman. “Like any parent, Haredi parents also want the best possible for their children and we understand the way we were raised and the way we are going to raise our child. We understand that he will have to work hard at an older age to get his English, and to complete core studies if he wants to become a doctor – and we are all aware of that and are ready to pay the price.”

What are the chances, then, that apart from individual cases, each of which is a unique story in itself, we will see more and more Haredim pursuing medical studies in the future? Yustman responds carefully: “We see an increase in demand, but to be admitted to medical school is very difficult even for someone who has a matriculation diploma and it is also a heavy financial burden for a Haredi family.”

And yet, he says, increasingly larger numbers of Haredim are beginning to study related fields that also require a high academic level: with help of the KEMACH Foundation about 2,500 men and women have already integrated into paramedical study programs, such as nursing, speech therapy, and occupational therapy, and over 80 have begun working in the life sciences, like biology, pharmacology and medical laboratory sciences. “A very high psychometric score is also needed be accepted into speech therapy at Hadassah,” he explains.

And perhaps in the end, the personal example and the initial breakthrough have the greatest power to bring about change: “After I graduated from high school and took the 5-unit matriculation exam on my own because there was no possibility of doing it in school, they introduced 5 units of math and English,” says Tsila. “It’s a big school and they can allow themselves to do it. They said: ‘We saw that it’s possible because one of our own did it.’

“One day when I was on the train someone stopped me and asked: ‘Are you studying medicine?’” says Segal. “‘Yes,’ I responded and she started asking me lots of questions, because she was also thinking about it. It’s great fun to help because I went through it, and it was hard for me and I didn’t have many people to consult with.”